What I Talk About When I Talk About Prompting

Foreword

This article is not about multi-agent orchestration or free-running autonomous setups. It's about meat-and-potatoes single-prompt tool calling. The kind of work where smaller, faster LLMs are often the only choice, and a single prompt can often suffice.

Although the current Overton window has shifted away, I still feel that this is a strong tool to keep in the toolkit, and there are various lessons I've learned along the way which may be useful for people stuck in a similar situation.

Over the past two years, I have built several user-facing features at Mercari using LLMs, spearheading the prompt shaping:

- Natural language driven search keyword and parameter generation

- Automatic generation of titles and descriptions for C2C marketplace listings from image inputs

- Generation of search related metadata from image and description inputs

- Automatic reply generation for sellers responding to buyer comments

These features form a pattern:

- The feature is user-facing

- Outputs are well-structured and well-defined

- Inputs are more often than not fairly loose, often free text

- Latency is at a premium; the UI needs to feel responsive, or batch jobs need to finish in time

- Cost per call is a real consideration at scale

- You want a well-defined prompt and code-based solution, rather than a more hands-off agentic flow

What follows are my thoughts on developing these style of features. Note that these are my thoughts alone, not endorsed by my employer.

Core Takeaway

TL;DR

- Start with the problem, not the technology.

- Gather real data.

- Define your outputs before you write a prompt.

- Build a tight iteration environment, don't overthink it.

- Play with it. Share it. Develop intuition.

- Treat prompts as code.

- Use the schema as a steering tool.

- Field names matter.

- Descriptions are mini-prompts.

- Turn your early data work into fixtures, judges and few-shot examples.

- The groundwork compounds.

- Love plain text.

- DIY tooling.

- Own your workflow.

- In the era of agentic coding, having everything local is huge.

- Tight, enjoyable feedback loops above everything!

Tight feedback loops are everything in this work, but you need to put in the groundwork to get there.

Without a clear problem definition and fit, and real data, you'll get stuck fast.

This article is about building both: the foundation that makes iteration meaningful, and the environment that allows you to close the loop.

Problem Fit

Before we dive in, I think it's important to have a quick way to gauge if this approach is the right one. We're talking INPUT->PROMPT->OUTPUT at its core, and squeezing that for as much as you can.

Good Signals

- Inputs are messy: free text, images, or data with an indeterminate shape (user-submitted descriptions, search queries in broken English, photos of unknown items)

- The transformation requires judgment that's hard to encode in plain-code rules

- A "Pretty good" solution is valuable, and mistakes can be caught, corrected or tolerated

- Simpler approaches have already hit their limits

- Latency and cost rule out multi-step chains or long reasoning

Should be avoided

- The transformation is describable as a clear algorithm

- The solution exists as another AI-centric approach, for example leveraging embeddings, a small pre-trained classifier or an off-the-shelf model

- Wrong outputs are costly and hard to detect

- You're reaching for an LLM because it's exciting, not because you need it

- You don't yet have a clear picture of your input space or what the output should look like

- You haven't mapped out the breadth of inputs or defined the shape of the output

Foundation Work

For the purpose of this article we will use a concrete example: a Hacker News profile analyzer.

Given a user's recent comments, generate a profile summary, extract topics, and analyze sentiment over time for visualization.

The input is free-form comments of variable length, with unpredictable topics.

The output is structured:

- text for display

- categories for filtering

- supporting quotes for extra context

Data Gathering

Arguably the most important step, since it informs everything else.

Gather a wide range of expected inputs based on anticipated user behavior. Real data, not toy examples. Be extremely careful not to cherry-pick "good" examples. You need the messy ones, the weird ones, the adversarial ones.

For our HN analyzer: pull actual comment histories. The prolific Rust expert. The lurker with three generic replies. The user whose tone shifts between helpful and combative. The troll. The brand new account.

Include abuse cases and scenarios where you want to gate early and avoid calling the LLM at all. Accounts with too few comments, Comments that are all just "+1". The over-promoter.

Output Design

From there, discuss and manually generate expected outputs for your initial input set. Then take some hammock time.

This is where you will begin to nail down the structure: what each part of the output will be named, and descriptions for each of those values.

For example, an early output shape for our use case might be

{

"summary": "Backend engineer focused on distributed systems...",

"expertise_areas": ["rust", "databases"],

"topics": [{"name": "rust", "count": 45}, ...],

"sentiment_over_time": [{"month": "2024-01", "avg_sentiment": 0.7}, ...],

"overall_tone": "helpful",

"confidence": "high"

}Now write it out for your edge cases. What's the output for the troll? The lurker? The user who shifts tone?

Doing this work now saves you from discovering these gaps mid-iteration. These manually-created pairs become your test cases, your few-shot examples, your evaluation sets.

This work is never wasted.

Initial Prompt & Schema Creation

With an idea of the inputs and outputs in place, go ahead and create:

- A simple system prompt

- A user prompt template to format the inputs you will receive

- An output schema, defined as a JSON schema or Pydantic model

Example: Output Schema (Pydantic)

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

class Topic(BaseModel):

name: str = Field(description="Lowercase, hyphenated topic name")

count: int = Field(description="Number of comments touching this topic")

class SentimentDatapoint(BaseModel):

month: str = Field(description="YYYY-MM format")

avg_sentiment: float = Field(description="Average sentiment, -1 to 1")

comment_count: int

class HNProfileAnalysis(BaseModel):

summary: str = Field(

description="2-3 sentence summary of the user's presence on HN. "

"Mention their expertise, tone, and notable patterns."

)

expertise_areas: list[str] = Field(

description="Up to 5 areas where the user demonstrates clear knowledge"

)

topics: list[Topic] = Field(

description="Top topics by comment frequency"

)

sentiment_over_time: list[SentimentDatapoint] = Field(

description="Monthly sentiment averages for charting"

)

overall_tone: str = Field(

description="One of: helpful, neutral, combative, mixed"

)

confidence: str = Field(

description="high if 20+ comments, medium if 5-20, low if <5"

)Example: System Prompt

SYSTEM_PROMPT = """You analyze Hacker News user profiles based on their comment history.

Be concise and factual. If there isn't enough data to make a judgment, say so."""Example: User Prompt Template

def format_user_prompt(user_input: dict) -> str:

comments_parts = []

for c in user_input["comments"]:

comments_parts.append(

f"### {c['story']}\n"

f"*{c['time'][:10]}*\n\n"

f"{c['text']}"

)

comments_text = "\n\n---\n\n".join(comments_parts)

return f"""# Hacker News User Analysis

## User Info

- **Username:** {user_input['username']}

- **Karma:** {user_input['karma']}

- **Account created:** {user_input['created'][:10]}

- **Bio:** {user_input['about'] or '(none)'}

## Recent Comments

{comments_text}"""At this stage keep it simple and get it done. This will all change dramatically, so just get something that looks reasonable for a few test inputs.

The goal is to have something to iterate on, and build tools to iterate with, not a finished product.

Importantly, having this in place also makes it fun! You have something to share, something to discuss and something to build tooling around.

Treating Prompts as Code

A quick but important side discussion.

Initially, I treated prompts as metadata. Files to be loaded in at runtime, and kept aside from the codebase. I've come around in my thinking though that for these kinds of systems, prompts should be treated as code.

They should be versioned along with the codebase. They should be reviewed along with evidence and reasoning as to why the wording changed. They should be tested using code-like machinery.

They should NOT be managed and developed using third-party tooling. Using any useful tool to get the job done is fine, but the main source-of-truth should live in your codebase.

This means:

- The same prompt definitions used in your exploration tools are the ones used in production

- Changes to prompts go through the same review process as other code changes

- Prompts live in your repository, not in a dashboard, not in a vendor platform, not scattered across notebooks

This approach pays off in consistency and traceability. When something changes in production behavior, you can trace it back to a specific commit.

The payoff is consistency and traceability. When production behavior changes, you can trace it back to a specific commit. When you're debugging a weird output, you know exactly what prompt produced it, not "whatever was in that config file at the time.

If you need variations on prompts, treat it like an alternative branch in your codebase.

Building a Rapid Iteration Environment

This is where the real work happens. You need an environment that covers the following bases:

- Ability to build inputs quickly and simply, and observe outputs

- Ability to run inputs in bulk and view results side-by-side

- Ability to adjust all the elements that affect output:

- The model

- The temperature

- The system prompt

- How inputs are templated into the user prompt

- The schema definition, including key names and value descriptions

All of these have bearing on the output. The JSON schema itself, the names used for keys, the descriptions for values; these all influence what the model produces.

The Minimal POC

Get a manually deployable minimal POC in place. In the era of vibe coding, this becomes fun and fast. Speed matters more than polish here.

Important points are:

- Use the same prompt code that will be used in production

- Allow everyone involved to tweak, explore, and discuss

- Produce shareable results as links

- Include the prompt used as data on the page

- Include the inputs

- Include raw outputs

- Include raw execution metadata like tokens used and latency

This becomes your central tool for collaborative refinement. When someone finds an interesting edge case or a particularly good output, they can share a link that captures exactly how it was produced.

Keep going

Don't stop at just one tool!

Create supporting tools to explore the edges of the problem.

If you're using images as inputs, explore how much information you can extract from an image using a multi-modal LLM before trying to use images as inputs. Give outputs for various image input sizes, or different temperatures.

Build a tool to try the same prompts across several models or temperatures at once and compare the results. Tabulate results across models, in a way that's easy to scan and read through.

These are all hugely informative, and will allow you to go back and debug strange outputs as you encounter them.

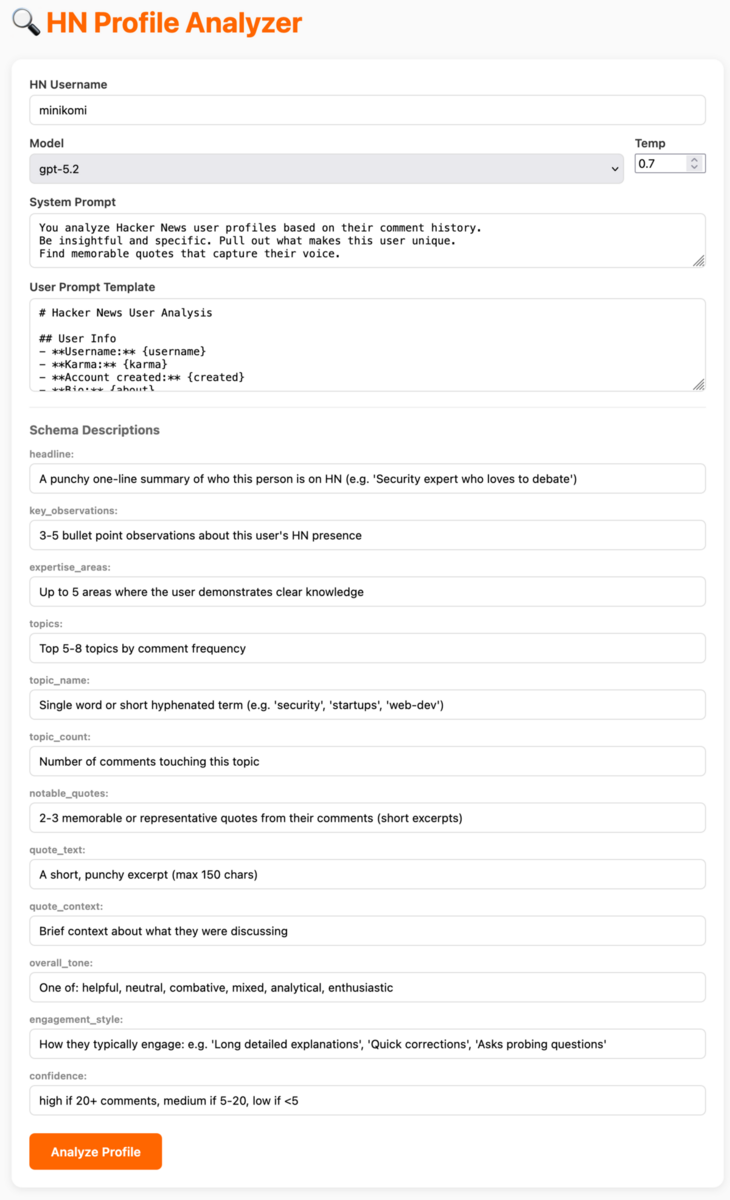

An Example

Your tool might take the form of a small web app with:

- Text input for the system prompt

- Controls for adjusting the preamble to templated data

- Temperature adjustment (for models where it is relevant)

- Text boxes for editing descriptions within the JSON schema

- Output displayed as close as possible to how it will appear in the final UI

- Raw model output, token counts, and response time visible

- A dropdown for selecting candidate models, or side-by-side comparison of outputs from multiple models

Playing here is important. Being hands-on and developing intuition for how inputs affect latency and outputs will inform everything that follows. In fact, in building the example app pictured above, I already adjusted my prompt schema to give a better-visualizable output:

Updated Schema

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

class Topic(BaseModel):

name: str = Field(description="Lowercase, hyphenated topic name")

count: int = Field(description="Number of comments touching this topic")

class Quote(BaseModel):

text: str = Field(description="A short, punchy excerpt (max 150 chars)")

context: str = Field(description="Brief context about what they were discussing")

class HNProfileAnalysis(BaseModel):

headline: str = Field(

description="A punchy one-line summary of who this person is on HN "

"(e.g. 'Security expert who loves to debate')"

)

key_observations: list[str] = Field(

description="3-5 bullet point observations about this user's HN presence"

)

expertise_areas: list[str] = Field(

description="Up to 5 areas where the user demonstrates clear knowledge"

)

topics: list[Topic] = Field(

description="Top 5-8 topics by comment frequency"

)

notable_quotes: list[Quote] = Field(

description="2-3 memorable or representative quotes from their comments"

)

overall_tone: str = Field(

description="One of: helpful, neutral, combative, mixed, analytical, enthusiastic"

)

engagement_style: str = Field(

description="How they typically engage: e.g. 'Long detailed explanations', "

"'Quick corrections', 'Asks probing questions'"

)

confidence: str = Field(

description="high if 20+ comments, medium if 5-20, low if <5"

)Testing at Multiple Levels

LLM outputs are inherently variable, but that does not mean we abandon testing. Instead, we build layers of tests appropriate to what we can reliably check.

Static Unit Tests

Create a layer of simple, fast-running tests that check for obviously bad behavior:

- Output length exceeding acceptable limits

- Response latency beyond thresholds

- Presence of forbidden words or patterns (regex-based)

- Malformed JSON or schema violations

These tests should run quickly and catch the most egregious failures before anything else. They are your first line of defense.

Integration Tests

After a round of interactive refinement, capture your identified good and bad input/output pairs in YAML files. These become pytest-driven integration tests that:

- Run against the actual prompt code

- Verify that known-good inputs still produce acceptable outputs

- Confirm that known-bad inputs are handled appropriately

- Can be extended as new edge cases are discovered

This creates a growing suite of regression tests that protect against prompt changes breaking previously working cases.

Sharing Work & Getting Feedback

The iteration environment can also serve as a communication tool.

Static Reports

Generate static HTML output of bulk runs that can be shared with stakeholders. Single, self-contained HTML pages with small JavaScript snippets for filtering or sorting by category are excellent for gathering feedback.

These don't need to be fancy. A table of inputs and outputs, maybe color-coded by confidence or tone, is enough for a PM or reviewer to scan through and flag issues.

Shareable Links

Try to make your POC hosted and sharable. Results should be shareable as links. These links should capture:

- The exact inputs used

- How they were templated

- The system prompt and schema at the time

- Model settings (model, temperature)

- Raw outputs alongside the "presented" output

This is vital for distributing the work of finding edge cases. When a colleague stumbles on a weird output, they can send you a link instead of a screenshot. You see exactly what they saw, with full context for debugging.

It also distributes the joy of exploring the solution.

Getting others hands-on early helps ensure you're solving a "right problem", not just a problem you assumed you had.

What To Iterate On

You've got your foundation. You've got your POC. You're running inputs and observing outputs. But what exactly do you tweak?

There are more levers than you might expect.

Easy first steps

| The system prompt | tone, constraints, instructions |

| The user prompt template | what context to include, how to format it |

| The model | different models have different strengths, latencies, costs |

| Temperature | lower for consistency, higher for variety |

The Schema

Field Names Matter

Key names "lead" the model toward what to generate next. If the model tends to output repeated keywords, naming the field unique_list_of_keywords instead of just keywords can help. The name becomes part of the context.

Descriptions As Mini-Prompts

The description field is scoped steering. You can use it as a mini-prompt for that specific value:

topics: list[Topic] = Field(

description="Single word or short hyphenated term (e.g. 'security', 'startups', 'web-dev'). Max 8 topics."

)Splitting up Pydantic schemas into parts helps keep things clear too; making them easier to define:

class Quote(BaseModel):

text: str = Field(description="A short, punchy excerpt (max 150 chars)")

context: str = Field(description="Brief context about what they were discussing")

class HNProfileAnalysis(BaseModel):

# ...

notable_quotes: list[Quote] = Field(

description="2-3 memorable quotes from their comments"

)Each nested class also carries its own field descriptions.

Guiding Values

Include intermediate outputs that aren't shown in the UI but improve coherence. Having the model output key_observations before generating the headline forces it to think through the material first.

Prompt-Schema Consistency

If your system prompt talks about "areas of expertise" but your schema field is called topics, you're creating friction. Align the language used in all pieces of your prompt.

From Iteration to Production

You've iterated. You've found a prompt, schema, and template that work well across your input set.

The work you did at the start - gathering inputs, manually writing outputs - pays off here. That data becomes the foundation for everything that follows.

Inputs As Test Fixtures

Turn your input examples into plain text fixtures in a predictable format. For example, plain YAML or JSON files, checked into your repo.

# fixtures/inputs/prolific_rust_expert.yaml

username: "rustfan42"

comments:

- text: "The borrow checker isn't the enemy..."

story: "Why I stopped mass-promoting Rust"

time: "2024-01-15"

# ...# fixtures/inputs/troll_account.yaml

username: "angryposter"

comments:

- text: "This is stupid and you're stupid"

story: "Show HN: My weekend project"

time: "2024-02-01"

# ...Expected Outputs as Judgement Criteria

The outputs you manually wrote during data gathering become your expected results.

They can be used to drive fast, static tests (like should_gate or comparing enum values), or confirm using simple LLM-as-a-judge expected results.

# fixtures/expected/prolific_rust_expert.yaml

headline_contains: ["rust", "expert"]

tone: "helpful"

confidence: "high"

topics_include: ["rust", "systems"]# fixtures/expected/troll_account.yaml

stop_word: "stupid"

should_gate: true # don't even call the LLMStatic Tests First

Start simple. Many checks don't need an LLM at all:

@pytest.mark.parametrize("case", load_fixtures("fixtures/"))

def test_analysis(case):

input_data = case["input"]

expected = case["expected"]

# Gate check - should we even call the LLM?

if expected.get("should_gate"):

assert should_gate(input_data), "Should have gated early"

return

# Run the analysis

result = analyze_profile(input_data)

# Static checks

if "stop_words" in expected:

for word in expected["stop_words"]:

assert word not in result["headline"].lower()

if "tone" in expected:

assert result["overall_tone"] == expected["tone"]

if "confidence" in expected:

assert result["confidence"] == expected["confidence"]

if "topics_include" in expected:

for topic in expected["topics_include"]:

assert topic in result["topics"]Fast, deterministic, no API calls. These catch the obvious regressions, and should be easy enough to run as part of your iteration tooling, or locally as you get closer to a new solution.

Fast is key. Fast is fun.

LLM-as-Judge for Fuzzy Criteria

For fuzzier checks, add an LLM-as-judge layer.

When I set this up, all judges share the same output schema and a single user prompt template which takes the inputs and outputs generated. I use a heavier model. I output a boolean and, if it fails, a reason and relevant snippet.

Judge Schema

Shared across all judges. JudgeReason forces the judge to

anchor its verdict to a specific snippet from the output, for checkability and to try and "downplay" hallucinated failures.

class JudgeReason(BaseModel):

reason: str = Field(description="Why this passed or failed")

snippet: str = Field(description="Relevant snippet from the output")

class JudgeVerdict(BaseModel):

passes: bool = Field(description="Does the output meet the criteria?")

reasons: list[JudgeReason] = Field(description="Supporting reasons")Judge Configs

Judges are purely about criteria and are kept as simple as possible.

USER_PROMPT = "## Input\n{input}\n\n## LLM Output\n{output}"

JUDGES = {

"mentions_expertise": {

"system_prompt": "You evaluate whether an LLM-generated profile headline mentions the user's area of expertise based on their comments.",

},

"tone_matches_comments": {

"system_prompt": "You evaluate whether the assessed tone matches the actual tone of the source comments.",

},

"topics_relevant": {

"system_prompt": "You evaluate whether the extracted topics are actually present in the source comments.",

},

}Fixtures

Judges are referenced judges by name in each fixture. You can select which to apply per-fixture, or have a series of default tests too.

# fixtures/prolific_rust_expert.yaml

input:

username: "rustfan42"

comments:

- text: "The borrow checker isn't the enemy..."

story: "Why I stopped mass-promoting Rust"

judges:

- mentions_expertise

- tone_matches_comments

- topics_relevantRunner

def run_judge(judge_name: str, input_data: dict, llm_output: dict) -> JudgeVerdict:

judge = JUDGES[judge_name]

return call_llm(

system_prompt=judge["system_prompt"],

user_prompt=USER_PROMPT.format(

input=json.dumps(input_data, indent=2),

output=json.dumps(llm_output, indent=2)

),

schema=JudgeVerdict,

model=judge.get("model", "gpt-5.2")

)Fixture/Judge pairs

Once you have your judges and fixtures in place you can run them as parameters to pytest:

def load_fixtures():

return [

yaml.safe_load(f.read_text())

for f in Path("fixtures").glob("*.yaml")

]

def fixture_judge_pairs():

return [

pytest.param(fixture, judge_name, id=f"{fixture['name']}/{judge_name}")

for fixture in load_fixtures()

for judge_name in fixture.get("judges", [])

]

@pytest.mark.parametrize("fixture,judge_name", fixture_judge_pairs())

def test_profile_judge(fixture, judge_name):

input_data = fixture["input"]

output = generate_profile(input_data)

verdict = run_judge(judge_name, input_data, output)

failures = [

f"{r.reason} | snippet: {r.snippet!r}"

for r in verdict.reasons

if not verdict.passes

]

assert verdict.passes, "\n".join(failures)The key shift is **flattening fixture × judge into individual parametrized cases**. Now your test output looks like:

PASSED test_profile_judge[prolific_rust_expert/tone_matches_comments]

PASSED test_profile_judge[prolific_rust_expert/topics_relevant]

FAILED test_profile_judge[prolific_rust_expert/mentions_expertise]DIY Tooling / LLMOps

Third-party eval platforms have their place, but they come with integration overhead, vendor lock-in, and workflows that may not match yours.

In the era of vibe coding and agent-assisted development, standing up your own test harness is fast. Plain text fixtures, pytest and a single web-app or multiple which support the team's exploration of the problem space.

These should be strongly considered, but loosely held. They should live in the same codebase, or the codebase should be designed such that the tooling can re-use the prompt definitions from the production code.

Aim to make the tooling easy to understand, but have depth for when you need to dig in and explore.

Sharability of results pays off in dividends always.

Few-Shot Examples

As your feeling for the problem space grows, your best fixtures can double as few-shot examples in the prompt itself:

def load_few_shot_examples(fixture_dir: str, names: list[str]) -> str:

examples = []

for name in names:

case = load_yaml(f"{fixture_dir}/{name}.yaml")

if case["include_as_few_shot"]:

examples.append(

f"Input:\n{format_input(case['input'])}\n\n"

f"Output:\n{json.dumps(case['expected'], indent=2)}"

)

return "\n\n---\n\n".join(examples)Same data, multiple uses. Your manually-written expected outputs become the examples that guide the model.

Documentation

Your fixtures become documentation too.

When another engineer picks up this feature, they look at the fixture files and immediately understand what kinds of inputs the system handles, what the outputs look like, what edge cases exist.

No separate docs to maintain. The fixtures are the spec.

Closing

That's most of it. The pieces reinforce each other once they're in place, and the upfront work pays off in ways that aren't obvious until you're deep in iteration.

Most of this reads like a normal approach to software engineering, and really, it is. It most likely resembles what you do when you interface with a legacy API or piece of code: gather examples, poke at the edges, build a harness, don't trust it blindly.

The difference is that the "code" you're working with is a language model, and the levers are a bit unfamiliar at first. Once you're comfortable with them, the schema, the descriptions, the field names, the prompt-template relationship, it stops feeling special and starts feeling like a base to build on and iterate.